MELANCHOLY and the infinite sadness of fashion

My friend Christian Weber, who in his own right has made a mark on fashion photography, sent me the recent Margiela campaign photos of Miley Cyrus from Paolo Roversi. I hadn’t looked at Roversi’s images in some time; I was immediately taken by the dream-like haze of darkness he creates. His deliberate occlusion of detail and familiarity to effect of something painterly and even otherworldly. Indeed, I was reminded of his exceptionalism, especially the way his precision with light masquerades as randomness. The images, in their intense patchwork of light and shadow, had me thinking broadly about the role of melancholy in fashion photography and how this affect becomes a mirror for fashion’s own interest in loss and ephemera.

In these new images—the brand’s first flirtation with celebrity—Cyrus appears like an apparition. She glows, spotted by light and coated in translucent body paint that echoes the Tabi boot. As a subject she is vulnerable and real, yet the atmosphere into which Roversi paints her is unreal. A subtle doubling occurs: at times it is difficult to know where Cyrus ends and the visual effects begin. Roversi’s gloom is undeniably beautiful, but his darkness—like much of fashion photography—often works as a shorthand for melancholy. Here, though, it suggests something more: fashion’s complicity with decay, resting quite literally in the shadow of its subjects. Roversi presses further, closer to memory. The dreamlike quality familiar to his work tips here toward nightmare, Cyrus’s pallid skin edging into horror.

And what is the nightmare of the fashion industry? Perhaps it is an awareness of its own ephemerality—as if it and its operators (photographers most certainly included) are conscious of the temporariness underpinning each piece, each season, each look. The lifecycle germane to fashion becomes a kind of memento mori of commerce. I wonder if in Roversi’s images he is hinting toward this truth.

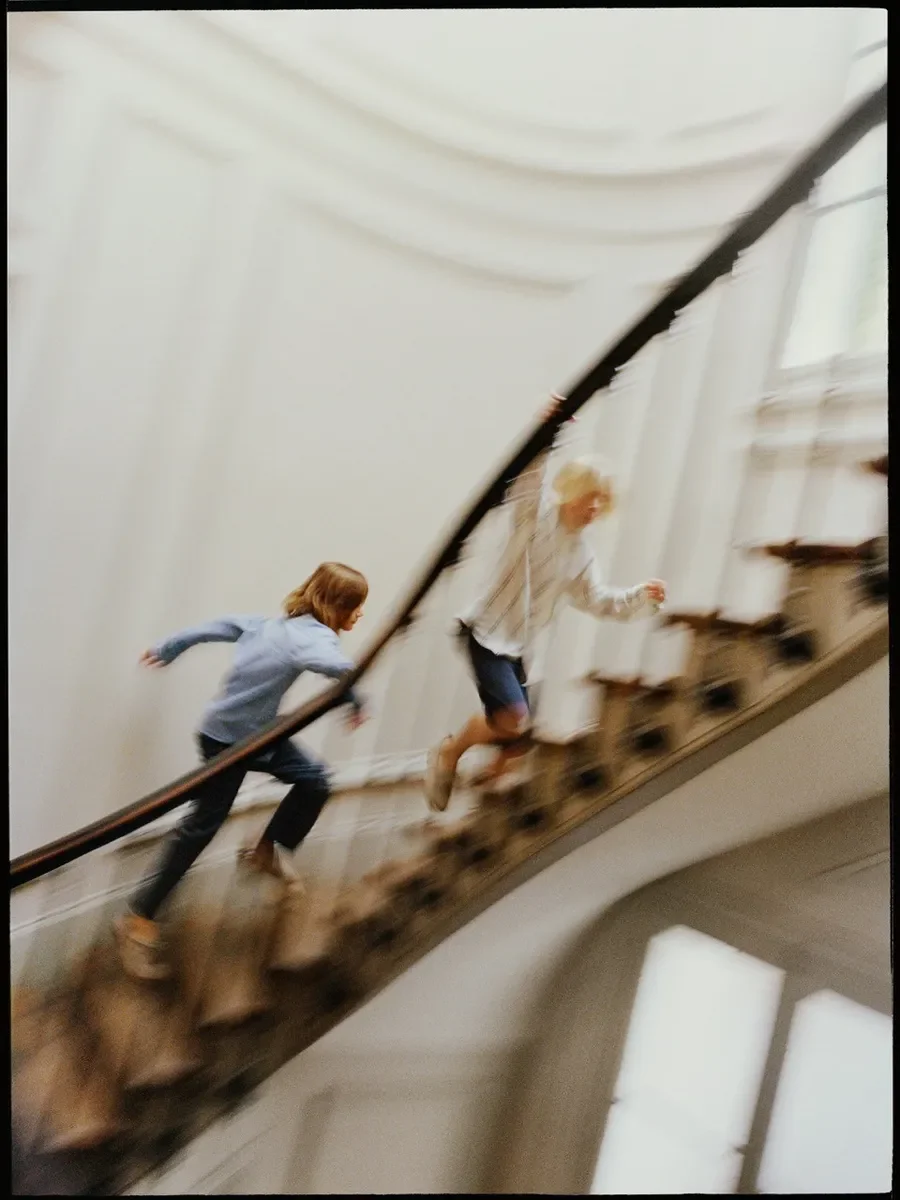

Looking beyond Roversi, I see a similar attention to melancholy in the pictures of Sarah Moon, whose images—especially the 8x10s with their slow, awkward shutters—feel more fragile, more proximal to erasure than Roversi’s. At times her subjects feel accidental, like people having stumbled upon an impressionist’s scene, mid stroke. Though Moon’s images have less visual heft, less clarity, they carry the same semiological weight in their appointment of (and perhaps invention of) these fashion cues.

I love her pictures. I love how the blur, as in her work for Dior, feels memorial. It targets a different kind of psychology than Roversi’s does. The Dior afternoon dress, for example, in full blur, regards the gown not as a precious fashion object so much as a notion. Mélancolie, the French cognate, resounds in her pictures. Her work somehow reminds me of Nicholas Alan Cope’s photographs for the Met, which, in their precision, read almost as a response to Moon’s fragile, technologically limited style. Dior himself once described fabric as “the sole vehicle of our dreams.” Moon, perhaps inadvertently through the medium’s limitations in the ’40s and her orientation toward the memorial, enacted this vision.

Barbara Tuberville, Circa 1980

Rasus weng Karlsen, Circa 2020

This preoccupation with decay and lifecycle had me thinking also about Deborah Turbeville’s Polaroids. Outside of her fashion work, Turbeville created a series of experimental snapshots that referenced her commercial images while attempting to create a new language altogether. The very technical aspects of the project relate to this discussion of melancholy: she scratched and distressed the Polaroid’s surface to uncanny effect. What emerged was a language of accident, but also of time. These interventions foregrounded the chemical fragility of the photograph itself—its decay folded into fashion’s own ephemerality.

Today, melancholy often appears as pastiche. Fashion marketing has become a referential machine of familiar ideas—ruined interiors, brooding models, dark light—progressing a language of mourning which the above artists have been honing for decades. That sadness and despair cling so naturally to the industry has everything to do with what we all feel any time a jacket seems senselessly tired in our closet; a sense that desire and accumulation are wrapped in the same fabric as decay. Indeed what Roversi’s light, what Moon’s color and Tuberville’s chemical manipulation reveal is not only subject wrapped in luxurious material, but an absence. Barthes sees this absence in his critiques of fashion and photography; his, “spectacle of absence.”

What’s interesting is that this mood is no longer the cool rejection of smiling faces and happy people; it has become their symmetrical alternative, every bit as conventional. If joy once looked naïve, melancholy is now rote. Both function as pre-scripted poses in fashion’s system of signs, shaping the mythology of the consumer. That is, different expressions of the same awareness that beauty, in this industry, is always already vanishing.