THE GENEROUS MEDIUM

On the fifth floor of MoMA, where I was this week with my son, a large Balthus painting, The Street, confronts us as we step off the escalator. At this scale and in the context of MoMA’s crush of tourists, the painting felt almost like an echo of the space we were in: banal, international, astir. However, like any Balthus work I’ve stood in front of, I was moved from ease to discomfort in the amount of time it took me to notice what was off about the picture. Here, a group of seven individuals mill about in a languid Parisian moment, while on the left edge of the canvas, a man and an adolescent girl are caught in an act of sexual violence; one rendered so seamlessly into the tableau that it almost disappears. Despite the way Balthus uses the reds to encircle the scene as if compelling us to look for help (or perhaps, from a Kitty Genovese perspective, to feel certain that someone will do something), he is able to hide the aberration among the lassitude of the rue Bourbon-le-Château. That the contingency of the tableau is altered with an image of activated sexual impulse, too, feels like a perfect precursor to his most popular and controversial and much more psychological works. The Street was made in 1933 and exhibited in 1934, and from 1936 to 1939, Balthus continued his exploration of sexual taboo, chiefly with a concentration on his pubescent neighbor, Thérèse Blanchard.

In Thérèse Dreaming (1938, above), Balthus stages psychological fantasy from multiple perspectives. Here, the young girl’s rapt gaze creates a distance between her inner world and the audience’s own subjectivity. Unlike The Street, any act of sexual decadence is shielded. Instead, we get an intimate but ultimately superficial invitation to what are the universal dormant sexual desires of pubescence—unarticulated and waiting. Thérèse is in repose, one foot propped on her chair; below her, a cat laps milk from a bowl. Her hands are clasped behind her head in a suggestion of satisfaction that completes Balthus’s obvious visual metaphor. Indeed, the work, in all its details, is unmistakably designed to evoke pubescent sexual latency. However, nothing here is puerile. Rather than trivialize, Balthus, in his mastery, takes this state of transferrance seriously and grants an opening which implicates the viewer in a similar way to The Street. However, where the earlier painting uses compositional rhythm and busyness to distract from the transgression, Thérèse Dreaming forces the viewer to imagine it. Here, Balthus weaponizes his classical techniques, in the era of Surrealism, to challenge our moral stability.

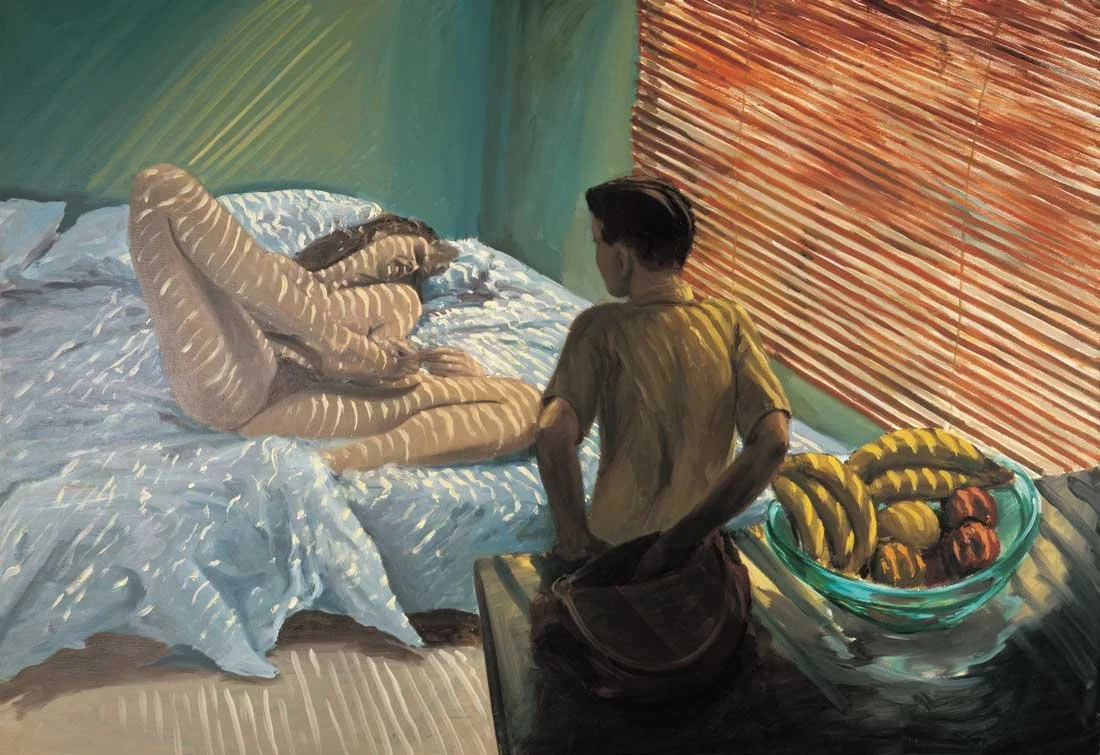

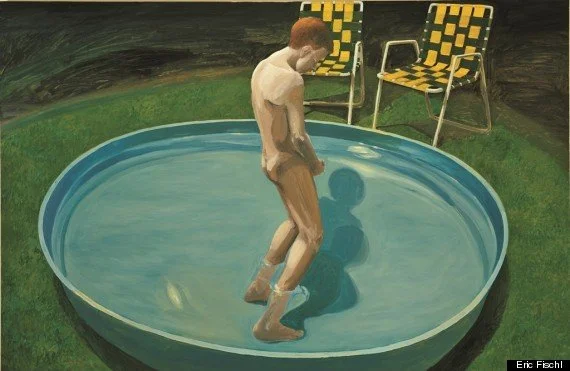

Each time I return to Thérèse Dreaming, I think of Eric Fischl—his Sleepwalker (1979) or Bad Boy—as the American suburban analogue to Balthus. Both artists use voyeurism to spy on our collective consciousness of teenage behavior. Like Balthus, Fischl, too, found drama in the unguarded prurience of adolescence—in the charged solitude of the bedroom or the backyard. Both articulate desire not in the explicit act but in its prior state, transforming our act of looking into something suspect. In this way, the long-standing public and private paradigm of painting is rocked from its core.

Photography is about this looking, too. Lee Friedlander once called photography a “generous medium.” By this he means that every image contains far more than the photographer intends. Unlike painting, the photographer cannot (in most cases) control the sum total of constituent parts of any picture; that is, the world and all its details happen to leak in, always. The punctum, to borrow Barthes’s term, arises from the studium. To this end, the unintended information in a Balthus painting might be the ambient moral complexity that seeps through his precision. Are we witnessing an aesthetic study of adolescent psychology, or a projection of our collective fascination? Our contact with obscenity, in Žižekian terms. To me, his canvases hold a kind of moral suspension in which expectation and exploitation blur. Of course, what his painting cannot contain are the biographical suspicions of his affair with another thirteen-year-old (not Thérèse, but Georges Bataille’s daughter) and the mild repercussions that followed—a pattern not far from that of another famous Polish artist. (Email me your guesses.) The French philosopher Sarah Kofman says of his critics that those who “find Balthus troubling, it is because adolescent sexuality is troubling in its ambiguity and transitoriness between childhood and adulthood.” At any rate, Balthus’s fascination with and depiction of adolescence, however puristic or open to it one might be, underscores the long-debated notion around moral complexity in authorship (I’m thinking here of Wagner!). Can a work made by an immoral artist truly be enjoyed?

I like to think that in today’s era, nothing is sacrosanct. However, it was only a few years ago that a group petitioned to have the painting removed from the Met. A generation after Balthus, among figures like Henry Rollins, Lydia Lunch, and Nick Zedd, emerged Richard Kern, who helped to define an underground cinema obsessed with transgression. I recommend this book. His films—Fingered, Submit to Me, The Evil Cameraman—replace Balthus’s painterly and figurative ambiguity with explicit confrontation. In his photography, Kern’s women—often young, posed in ways that blur the line between agency and objectification—are half-dressed, smoking weed, or performing in overtly sexualized ways. They inhabit tight apartment interiors and are lit by flat, sharp light, which I tend to prefer in his adoption of digital imaging. In Pot Smokers, they light blunts; in Medicated, they hold pill bottles and birth control in front of their stomachs. In Guns, the motif continues. The scenes hum with erotic, proximally pornographic charge, but what distinguishes them, especially in conversation with Balthus, is that Kern’s subjects stare back.

Where Thérèse’s eyes are closed, Kern’s models overwhelmingly meet the audience’s gaze head-on. The power dynamic shifts to the extent that the viewer, for once, becomes exposed. In doing so, Kern doesn’t shadow erotic tension with clandestine tonality but confronts it, reflecting and perhaps acknowledging our sexual impulse and desire to see and be seen. I feel strongly Barthes’s accusatory notion of the punctum here.

It is understood that Balthus borrowed Thérèse’s ultimate pose from Man Ray’s 1935 photomontage (the image is under copyright and nearly impossible to find online), which itself follows a longer tradition of transgressive depictions—from Munch’s Puberty to Otto Dix’s Little Girl and Schiele’s Young Girl. These images share a fascination with adolescence as a site of latency, where the sacred and the profane coexist. Each artist tests the same fault line: what happens when private becoming is rendered public? In this sense, Balthus and Kern, though separated by half a century, draw from the same genealogy of looking—one that treats innocence as more than a subject but also as a condition to scrutinize.

And how, then, to situate Sally Mann? In works like Virginia at Four, she embraces the publicity of making an image. The photographs of her children do not hide the apparatus of looking; they acknowledge it. While the Balthus/Fischl gaze is undeniably about surveillance and Kern’s about mutuality, Mann’s, I think, attempts to dismantle it all with directness.

As John Berger reminds us, images inherit their structure from earlier forms. And to take this further, adapt to time. His comparison between Alberto Korda’s Che Guevara (scroll) and Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp demonstrates that even the most political photograph borrows its power from art’s sacred archetypes. Both Balthus and Kern operate within this continuum: each testing how far beauty can trespass before becoming obscene, how much a single image can tell us about the ethics of seeing. Art is not about resolving morality.

Friedlander’s notion of the generous image feels ever-pertinent: that in the surplus of content there lies room for confusion, ambiguity, and projection. The artist, like the viewer, is implicated by what exceeds their control. I want to say that what any work ultimately reveals is that its ethical life begins when it is out in the world, but I’m not so sure that’s true. Those Surrealists were a bunch of pervs. However, they were a community. They were setting out to transform consciousness and point to the slow creep of centralized power structures, puristic values, alienation, and colonialism. As I was writing this piece, I used Chat GPT to remember the title of the Eric Fischl painting. I could neither remember the name of the painting, which I first saw in an art-school lecture, nor the artist, and relied on a terse description. “…it’s a painting of a boy in the backyard of some suburban home, brightly lit, in an inflatable pool, potentially masturbating,” I wrote into the chat. As the machine began populating the dark window, it interrupted itself with red letters to let me know I had violated the community guidelines. One of the reasons I’m so happy that the Balthus work did not leave the Met is because censorship and the guardrails of expression are rarely altered in a violent shift, but rather through a steady and imperceptible creep. One of the reasons I love the Surrealists more than the Futurists because I am not a fascist. That, in the context of an essay on moral complexity in art, this query would be flagged proves the point. I often use Chat to brainstorm and begin research. I treat it like a dynamic search engine. I use it to write emails from bullet points, which likely get broken back to bullet points on the other end. But I never asked to be a part of this community, really.