THE ECSTASY OF INFLUENCE

In his essay challenging Harold Bloom’s concept around the anxiety of influence, Jonathan Lethem proposed the ecstasy of influence in his own collage-text style work, the form itself making a case for borrowing as a requisite creative act. Unlike Bloom’s perspective that art making in the modern era is a burdensome misreading of the past, Lethem’s work posits something opportunistic: that the whole of art history is a creative cave to mine. I’m curious here about the conditions of copying and how, in the present era of saturation, copying may be more of a thoughtless and compulsory act versus discursive tool.

Looking to the past is at the core of this blog and yet, I too have suffered from a Bloom-adjacent reticence toward Influence. Does my adoration ever progress toward unconscious theft? In the first painting school I attended, one professor, the most adroit of them all, instituted a weekly routine of copying drawings and sculptures from the masters. In that first week I recalled the hours I had already spent copying as a child; tracing the hard black lines of Mickey Mouse on letter head print outs. Years later, on the floor or on wooden benches at the Gardner or the MFA, or before the washed out glow of flickering slides, we would make our own images of other finished works. To the class, the practice incited a bitterness that, after some time, contended with admiration. To this professor, the past was an eminent fount of reverence. In time we would admire Vermeer’s light, analyze Titian’s musculature, marvel at Tintoretto’s depth, and become lost in the gaze of Rembrandt’s elegiac self portrait; we would speculate at exactly what point on the canvas Sargent might have started his underpainting for say, El Jaleo, where the fold created by the dancer’s tucked hand is like a fulcrum to the painting’s masterful balance of detail and ambiguity. How Sargent is able to create harmony without giving everything the same level of visual attention is his great gift.

It seemed that the longer I would look in earnest at any one image or sculpture—objectively considered a masterpiece—the more I would start to understand the constituent parts of beauty. Similarly, in literature, to read Lispector, Balzac or Faulkner and rewrite whole paragraphs, word for word, (which, shamelessly, I have done), is to study, if psychotically, the way great ideas and voices are formed. For example, to read the opening paragraph to A Farewell to Arms is to understand literary economy, the same way to dissect any chapter in Lost Illusions is to brush up against authorial mania. By this math, the tenets of creative generation have as much to do with copy as they do originality.

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterwards the road bare and white except for the leaves.

Hemingway.

There is something uneasy in the Los Angeles air this afternoon, some unnatural stillness, some tension. What it means is that tonight a Santa Ana wind will begin to blow, a hot wind from the northeast whining down through the Cajon and San Gorgonio Passes, blowing up sandstorms out along Route 66, drying the hills and the nerves to the flash point. For a few days now we will see smoke back in the canyons, and hear sirens in the night. I have neither heard nor read that a Santa Ana is a “condition of the nerves,” but I know that some definite, though possibly imaginary, connection exists between the hot dry winds of the desert and the uneasy moods of those who live under them.

Didion.

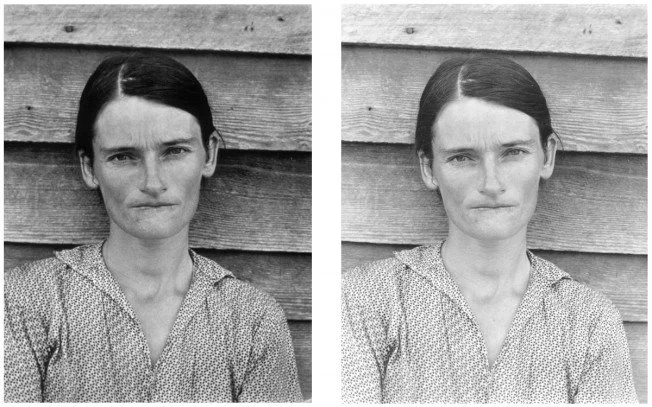

In his essay, Lethem shows how the act of copy can become the art of copy; (and here I suggest both definitions of the word). His work shows how borrowing can reify a concept to the effect of new art. Other artists have done this too of course. A thrilling example that comes to mind is Sherrie Levine’s After Walker Evans. Part of the 70s and 80s “Pictures Generation” artists, (Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince), Levine created a new sort of metatextual post modernism with this project. Here, Levine makes pictures of Walker Evans reproductions from his iconic depression era series, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which is, in my opinion, the most iconic example of reportage from this era—this despite the subjectivity Agee, the project’s writer imbued. The two men were sent on assignment (ultimately rejected) by Fortune, to document the lives of impoverished sharecroppers in Alabama. The final 600 page work follows three families and their dealings with the Great Depression. Years later, Levine’s images of the images became something much greater than facsimile. Saliently, her photo of Allie Mae Burroughs is, in my opinion, a high concept feminist masterpiece.

Around the same time, the art world also saw Andy Warhol, Richard Prince and countless others whose works materially repackaged a past of consumer and artistic images as a commentary on the present. What I think these artists did also, is expose the social fiction of originality and as Lethem’s work suggests, placed prior art on the same inspirational plane as anything else. As an artist, there is indeed a freedom in this perspective. At The Modern in Fort Worth, a magnificent museum designed by Tadao Ando, Jenny Saville’s equally monumental paintings confronted me with the full force of their heft and brutality. Amongst her gruesome crime scene images and grotesque autobiographical depictions of motherhood, were quieter paintings, such as her self portrait “after Rembrandt.” Thinking about this essay, the vocabulary of copying became more apparent with every turn through Ando’s pockets of concrete light. The giant Motherwell seemed like an echo of the low contrast Picasso etchings. Even the giant Keifer—whose work I often regard as singular—when proximal to the Pollack, seemed suddenly derivative.

And then there is Serra. Approaching the museum, one is inevitably greeted by the priapic tower of orange sheet metal, inside of which, the sound of one’s own breath is carried toward the heavens, toward the portal formed by the weathered steel. It is an endlessly tall and obviously masculine work that, like Running Arcs for John Cage at the Gagosian and like Equal, the four irregular hunks in the Museum of Modern Art, Vortex in Fort Worth denies recreation in its arduousness. Like Matthew Barney, Keifer and others who work is situated within this genre of the monumental, their singularity is borne out of the difficulty in their creation.

Great works are often characterized by their originality. It is the sought after prize of criticism by most artists. But, perhaps there is something of a myth to originality, too. Inspiration is no longer in the shadows of one’s personal art book collection or vintage fashion magazines. The internet, especially social media in the way creatives use it as a showcase, has turned the garment of inspiration inside out and therefore, exposed the collective propensity for copy. Why does this feel like such a transgression given what we know about this legacy of copy in art history? Perhaps it is the lack of intimacy, the saturation. Copy is no longer an act between two artists or something that happens within a tight milieu. One needs to look no further than a Pinterest page to see the way sameness pervades. Two years ago, when every other ad campaign and fashion film hosted a Black cowboy, I felt like screaming. While images become data points in our collective exchange, they also point to the perfunctory orientation toward copy.

In my twenties when social media was nothing like the ubiquitous monolith it is today, I wanted to print out Instagram pages at random and wheat paste them around New York City, exposing hopefully this collective predilection to repeat. I wanted to melt the public-private membrane in a way that would provoke. I thought that with this work I would be in conversation with Phillip Lorca diCortia’s Head’s, with the unwilling participants. As I was preparing, I discovered Richard Prince’s “New Portraits” project, where the artist printed his own Instagram feed out, which in the context of a Gagosian gallery, became art and recoiled in my lack of originality.

Beyond the myriad instances of copy (accidental and deliberate) between artists and online, there have also been instances of self-copy. This perhaps proves the utility of the act itself. I’m thinking of two instances in film in particular, where a director chose to recreate his own work. In 1997, Michael Haneke made a German film about audience complicity in media culture, Funny Games. The picture is a brutal portrayal of classical home invasion violence, which attacked middle class banality and fear as a product of violence in the media. Ten years later the director recreated his film, shot for shot. The differences were actors, language, location, and of course, audience. In the same way a novel might be translated from German, Haneke makes this possible in film, pointing to the significance of contextual shift. Through the translation, the same film product is able to expose the cultural differences between an exclusively German/Austrian and American perception to the same subject matter. That is, the replication heightens the conceptual framework rather than dilutes it.

In Vertigo, Scottie as played by James Stweart says to Judy (Kim Novak), “One doesn't often get a second chance.” However, Hitchcock was afforded a second chance with his remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much when David O’Selznik thought up the idea for the recreation. Many scholars have noted Hitchcock’s propensity toward self-recreation in general—something I would refer to as artistic growth! But in this spirit of hyper analysis, there is a centrality of reprocessing individual shots and transitions across his oeuvre. The echoes of certain close ups, certain Kuleshov practices of a woman screaming in close up and then a body and so on. Similar to Funny Games, The Man Who Knew Too Much is about the invasion of violence into the middle class and how a relationship might be subsequently contorted. As Truffaut notes, “the first version is the work of a talented amateur and the second was made by a professional."

While writing the last paragraph, I opened my phone and scrolled for two minutes on Instagram. I saw a strange film by A.G. Rojas about ICE agents. I learned about the death of one of my favorite Iranian actors. I saw a fashion ad that looked like many other fashion ads. In two minutes I was hit with many ideas about life that might inspire ideas of my own, (my own?). The problem with the present saturation it seems is knowing how parse. Writers talk endlessly about this dilemma: the overheard conversation that becomes dialogue, the private text thread that seeds a scene. Artists, by nature, experience life a little exploitatively. I’m not immune. Sometimes I worry that my own compulsive documentation has warped my son’s sense of experience—everything, to him, is a photograph waiting to be made. Although perhaps this too is an influence: he understands intuitively that I tend to photograph the things I love.

I will admit that after standing in a painting studio for many years at a minimum of five hours at a time, the discovery of photography has become a natural analgesic. That to say, it often provided a more direct route to something that felt complete. I could reach the end product of image-making more quickly and therefore, could be prolific. At times I think about this shift from painting to photography as a giving in to temptation because no matter how far I attempt to push my image making, the photograph feels lazier than the painting. Gradually, it seems, we are being corralled into a creative mold and corrected over time. I feel this in the passive aggressive blue squiggles under certain sentences that this Google Docs suggests are too long. Style is being replaced with efficiency. Capitalism insists upon this efficiency because in the absence of personality, we can send more emails, be more in a writing that feels productive.

Perhaps where I am going is the same place Barthes arrived years ago with the death of the author. But the dilemma today is less situated around some quest for peer-deemed originality as much as it is a refutation toward being artificial. AI is progressing this myth of originality in a new way. Images and texts are being generated, which feel finished, replacing the need even for copy itself. Now artists are tasked with masking the traces of AI in their work versus the work of other artists. It is a palimpsest of ourselves with obvious consequences, chiefly futility. And yet, I see hordes of artists and writers relying on AI to outsource thinking and craft and production. This is especially frustrating with writing. In its ubiquity, writing feels accessible. And yet, in tension with the way we feel about it, writing is a difficult and brutal act. To compose is to be patient and in time.

My prior film about my friend Leah’s 756th day on parole, the single take narrative I made on my friend’s harrowing encounter with a homeless man, the young sociopath in upstate New York. None of these experiences are my own and yet I have authored all of them. Filmmaking, like photography, even like painting, is a sort of habitual borrowing—better, skimming—from life, often others’. Earlier this fall, I finished production on a feature film on my father. While not the motivation for the film, it was on some level a rebellion against what I have assailed above. With the camera never leaving the interior of his taxi, the film form, as well as the process became hermetic. For many long nights, crammed in the back of his Rav-4, I was sealed off from this noisy, data-saturated exterior. But then this type of film also falls within a genre of other personal documentaries and therefore risks being labeled unoriginal. From Anges Varda to Kirsten Johnson, the act of pointing the camera inward is nothing new. As I was making the film, I reflected on the way filmmaking can feel like one giant theft; that despite how copy is a condition that is seemingly baked into art, film, in its fidelity to reality, seems like the most potent form. However, that an AI cannot sit in the back of my father’s Toyota with a monitor and watch his face, which looks like my face, concentratedly driving past the Verrazano at three in the morning, is the real ecstasy of influence.

I will have Chat check this for typos.