SNOW, INDIANA, GOLDIN, BUT MAKE IT TELLER

This week, I’m looking at the snapshot. A category of photography that, by many, has been dismissed as lazy or casual. But it’s this rejection of form and polish that gives the approach its magic and charm. Bringing a few artists into conversation, I am curious about the intersection of structure and spontaneity and how, like many other artistic modes, the snapshot has been adopted for commercial gain.

andreeljutica.com

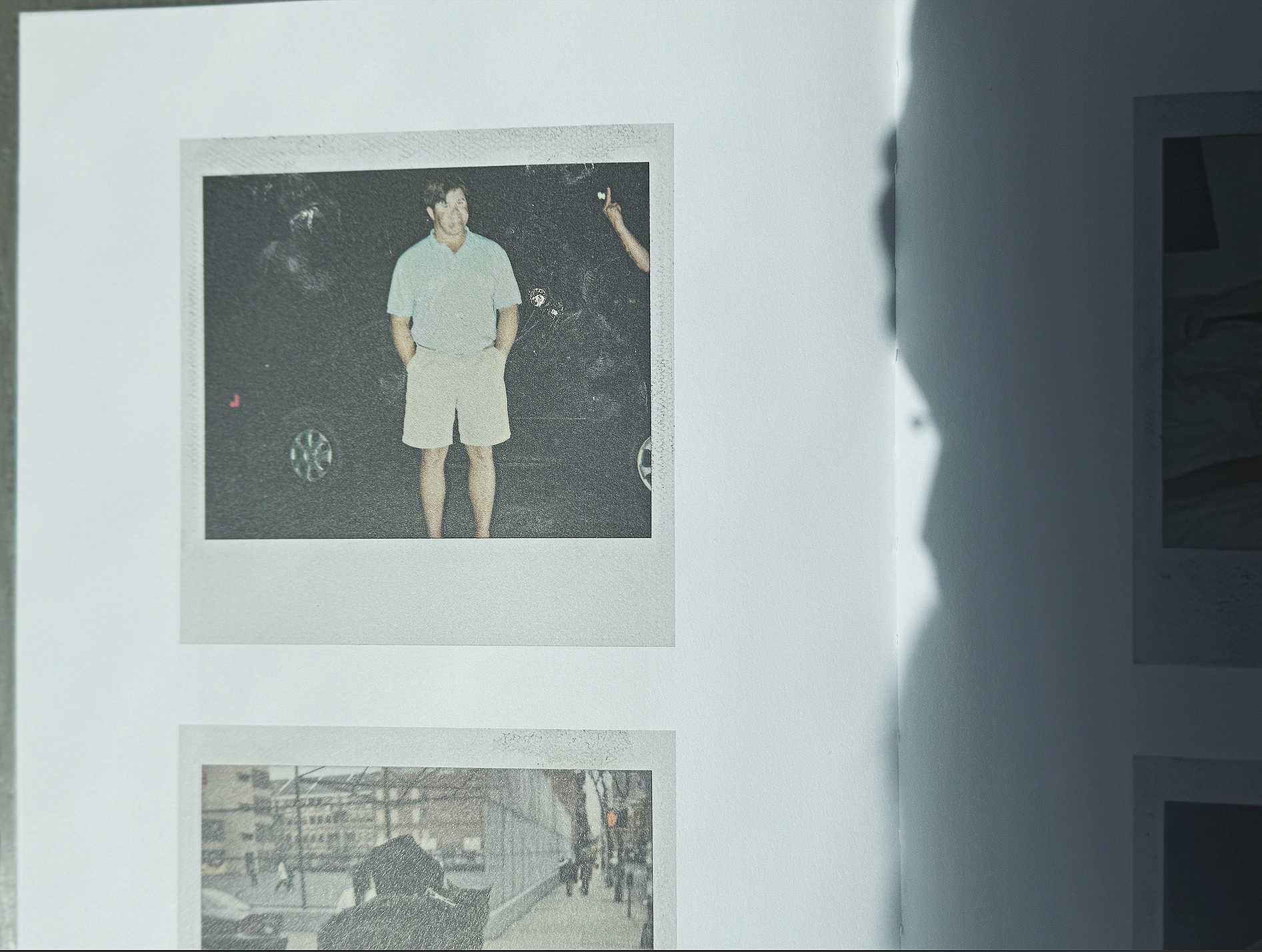

There is an image in I Love You, Stupid!, the DAP-published work of over 400 original Dash Snow Polaroids, scanned at actual size, taken between 2000 and 2009, where an awkwardly placed middle finger caresses the right edge of the frame. In the dead center of the dirtied, once-white Polaroid border, a complicit yuppy stands for the camera, his blue polo tucked neatly into beige shorts. The image, formalistically unremarkable, if sloppy, feels like a distillation of Snow’s larger project—if one was ever in mind. A rejection, perhaps repulsion, from systemic normalcy. The book, which followed his posthumous 2012 exhibition in Berlin, is filled with vile bohemian excess. It is a sprawling portrait of the many victims of the late punk lifestyle in New York at that time. With its concentration on homelessness and derision, it becomes, to me, a portrait both of the willing participants in counterculture and those unwillingly caught in its orbit; that is, a sociology of excess, human and otherwise. Among the fucking, snorting and puking, there are also pages of people sleeping: women passed out and pregnant, men in a daze on vacant street corners, the unhoused collapsed and stripped. Interesting how inactivity reads as rebellion. In sum, these images—often brutal, though sometimes tender, (such as those of Snow with his daughter)—point to punk’s repulsion from the normal order.

Formalistically, with its immediacy and function of continuity, the Polaroid enables this project. It is the punk’s weapon of choice. And the backdrop of 9/11 at the onset of his photography “career” in earnest also feels like an important note, as if to satisfy or validate his instinct toward capitalistic destruction. In sum, Snow’s work is about excess. His images point to an overflow of emotion, rebellion, to the human artifacts that exceed the volume of societal normalcy.

Beyond Snow, Goldin’s work has always been a benchmark of form and content for me. Her photographs borrow from punk’s immediacy, but their deeper refusal is anarchic in spirit. Her images are often deceptively simple yet filled with the sort of emotional potency that has always torn into my jealousy centers as an artist. If Snow’s work was about speed and life as a flash of drugs and impulse, Goldin’s is about duration and the emotional backlash of a similar lifestyle. Among many other readings, her project is about dismantling the classical notions of portraiture, something that once fixed dignity to power. Goldin fixes her subjects to disarray. This, I think, is the essential punk spirit in her work.

In fact, Ballad is a giant reclamation. Its rejection of the standard practices of artistic extraction—particularly of the marginalized—through her naming of friends and subjects, satisfies this reversal of priority. Goldin’s essential punk tendency lies in the way she dignifies social outcasts. Ballad, while durational in many respects (from her local and inclusive exhibitions to the span of years it covers), is ultimately a snapshot of cherished relationships. Here, Goldin turns care into something anarchic: a resistance movement fueled by love.

If Snow’s work projects societal excesses and Goldin’s insists on survival, Jürgen Teller demonstrates what happens when punk’s visual vocabulary is folded into commerce. His subjects enact the awkwardness and unrefined posturing of the snapshot, but they are in service to the very apparatus it once resisted: luxury fashion, glossy magazines, celebrity, commerce. The accidental and contingent becomes intentional, a way of staging effortless fashion and cool.

Wolfgang Tillmans pushes this even further, softening punk’s raw immediacy into something luminous and, at times, inoffensive. His photographs are technically brilliant, as is his compositional vision, but the MoMA exhibition To look without fear, for example, was almost comic in its overreach. What fear is attached to the sunlit apple on a table? (I love Tillmans, for the record.) His images retain their magic, but institutional framing demonstrates how quickly rebellion can be metabolized into cultural banality.

As Baudrillard said, “The only weapon of power, its only strategy against this defection, is to reinject realness and referentiality everywhere, in order to convince us of the reality of the social, of the gravity of the economy, and the finalities of production.”

Teller often seems to laugh at the whole program; his absurdity undercuts the industries that embrace him. Tillmans, alternatively, is canonized as a kind of soft prophet of the everyday. Taken together, they remind us that no aesthetic remains insurgent for long. Once effective, it is swiftly recruited by the very institutions it once attempted to reject.

Which is why Gary Indiana’s voice still matters to me. Writing in the Village Voice during the very years these aesthetics were taking shape, his prose was its own form of snapshot: quick, cutting, contemptuous of the establishment. “The power shows I’ve seen looked manipulated, paranoid,” he wrote in 1987. Indiana refused polish in language the way Snow, Goldin, Teller, and Tillmans refused it in image. His skepticism remains the necessary counterweight, reminding us that every style—however resistant—will eventually be recruited, and that critique must keep pace with its absorption.