A Lesson on Repetition, on Repetition

There is a moment approximately ten and a half minutes into The Exterminating Angel (1962), Luis Buñuel’s twenty-fourth film of his career and final Mexican production, where the sixty-two year old master of craft allows a maundering boom mic to penetrate the frame’s lower third in a languid creep. It is unclear if the servant character in the foreground is aware of its presence, or if in his downward gaze he is simply avoiding the persuasion of an anxious Leticia (played by Silvia Pinal), to work through what he seems to understand will be an enduring night. Within the context of a film more attached to narrative sobriety than this one, such a transgression might be derided as a strange production mishap—inconspicuous as it appears—or perhaps more leniently, prepare a certain audience for an introduction to the documentary form; however, in this film, replete with aberrations on reality not short of a bear clambering onto a chandelier or an autonomous and disembodied hand roaming the floorboards, this singular appearance of the mic ultimately folds into recurring obscurity like a strange highway sighting in a passing car.

By this point in the film, the guests of Leticia and Nobile’s (Enrique Rambal) dinner party have begun to arrive, (twice, in fact), the audience has been privy to farm animals sequestered under a butcher’s block in the kitchen and the general sense of film space and time have been manipulated to some unnerving and perhaps confusing effect. But there is something embedded here, more than quirk, in the presence of the boom mic. Much like the protagonists trapped within their own social apparatus at this dinner party, to the highly attuned, it feels as though, in this moment, that the set itself is aching to escape from its own institutional container: i.e., the production. It is as if the film and its makers are unable to remain behind the wall of fiction. Brief as it may be, I think that this gesture portends the larger attitudes of the piece as being an anti institutional symbol both in form and in content. In form in that it blatantly rejects the institutional mode of representation of the era’s predominant film style, and in content through its direct provocation of societal classism, in a way which ultimately and surreptitiously points a finger at the audience as well.

Through satire, The Exterminating Angel is an absurdist vilification of institutional power and a sarcastic condemnation of the tendencies that it invokes. In this case, the institution under the microscope is the bourgeois class. In his critique, Buñuel effectively merges the ethnographic with the hyperbolic to the effect of a strange and nearly science fiction reality. What begins as an anodyne dinner party amongst a Mexican high society, one that film producer and critic Arturo Ripstein considers to be a “(sic) false recreation of Mexican aristocracy,” and that Buñuel claims to have modeled after English nobility, ultimately erodes into a base speculation on the human response to crisis, with a particular focus on the thin performance of etiquette. At one point in the film, shortly after the dinner guests have discovered that they are, for whatever reason, unable to leave the living room, Nobile is offended by one guest’s removal of a dinner jacket; this despite going hours without water or food and not long before the group is sacrificing a sheep around a fire of splintered furniture.

Before long the farm animals which were irrationally parading the interiors, conduct themselves with more decorim than the human guests, who can at certain points be seen crawling on all fours, praying to chicken feet and chanting Masonic hymns to an absence. In fact, as Conrad Randal points out in his Cineaste article from 1977, A Magnificent and Dangerous Weapon: The Politics of Luis Buñuel’s Later Films, the filmmaker claims to have, “done his revolutionary duty in dealing a blow to the bourgeois optimism…[of a certain period]” (10). It seems clear that for Buñuel, the requisite behaviors ascribed to places like the church or the bourgeois class should be scrutinized at the very least, and at most, perhaps burned down in a ritualistic blaze.

The story which in some ways is akin to Sartre’s No Exit—though later clarified by Buñuel in a Criterion interview accompanying the DVD as being only motivated by Sartre’s notion of l’enfer c’est les autre gens, (hell is other people)—is contained to a few locations in addition to the living room. There is the kitchen where we first meet Leticia, the salon where Nobile iterates the same welcoming speech twice and the dark closets within the living room that serve as bathrooms and the event space for two guests’ sexual assignations and eventual death. The audience also sees the outside world where those willing to intervene are afflicted by the same inexplicable inertia vis a vis the mansion. Finally, (for a few brief moments at the end), the audience is brought into a church that ultimately falls subject to the mystical entrapment. What is explained by the filmmaker himself, as delivered in film critic Marsha Kinder’s Criterion essay The Exterminating Angel: Exterminating Civilization from 2009 as, “the story of a group of friends who have dinner together after seeing a play, but when they go into the living room after dinner, they find that for some inexplicable reason they can’t leave,” is far from simplistic in its observance of societal tendencies. Paradoxically, it is the film’s simplicity in form and concentration to essentially one environment that offers its complexity in style and inherent rebellion.

This circularity or cellularity to the film’s form is antithetical to the surrounding Hollywood norm of the three act plot or even to the supposedly progressive cinematic movements like Italian Neo Realism, which Buñuel also criticized for its saturation of sentimentality. Hollywood especially was an institution against which he would actively repel as illustrated in a 1958 article entitled, The Cinema, Instrument of Poetry, where Buñuel writes of the Hollywood detective story:

“The structure of the story is perfect, the director is magnificent, the actors are extraordinary, the production is brilliant, and so on and so forth. But all this talent, all this savoir faire, all the complex activities that go into the making of a film have been placed at the service of a stupid and remarkably base story” (113). And more clearly later on, “if we wish to see good cinema, rarely will we encounter it in major productions…” (114).

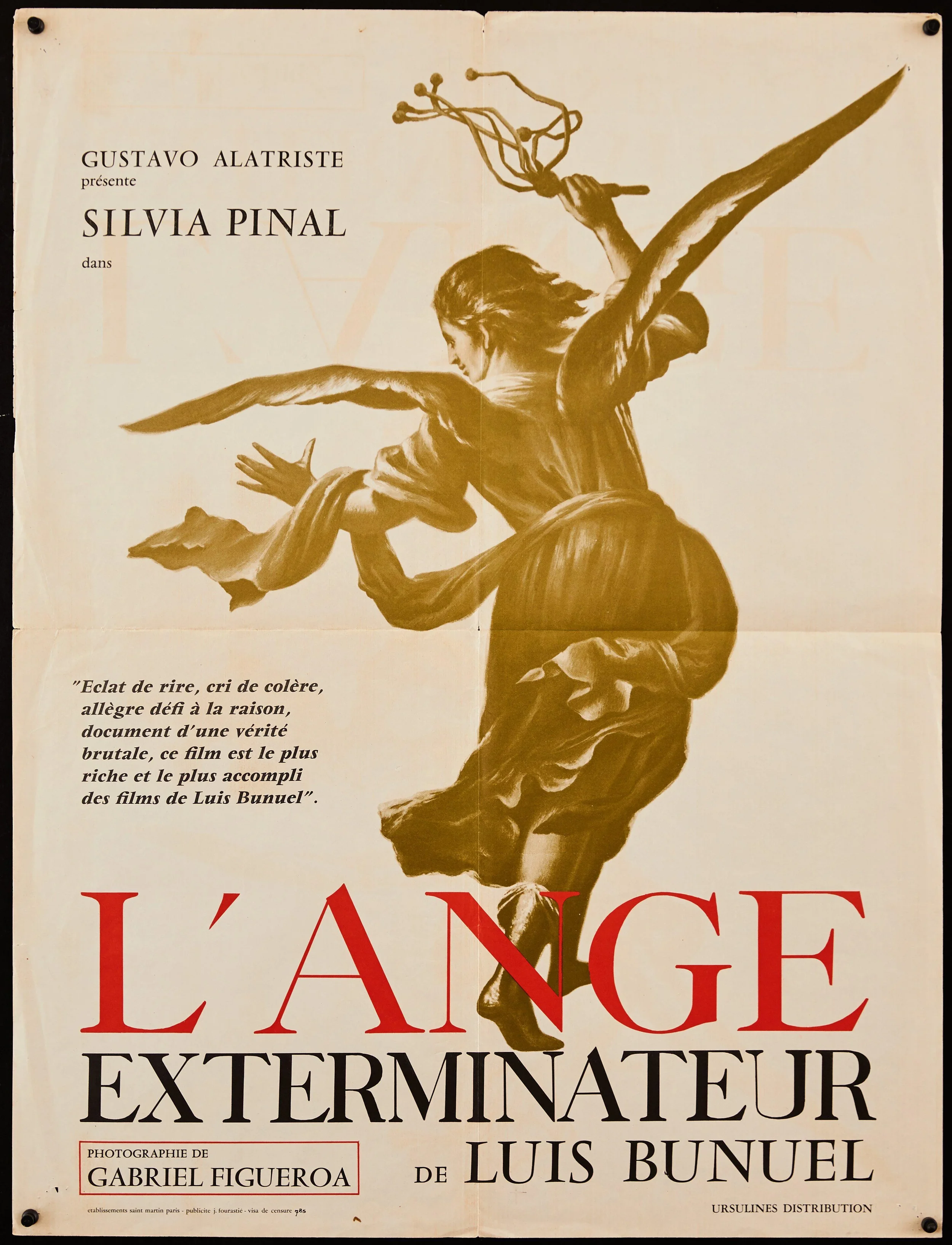

But I am wondering here about the motivations for Buñuel’s stylistic provocations. Is this push toward obscurity mere rebellion in an effort to present something new? Interestingly, prior to making The Exterminating Angel, Buñuel suffered an artistic trauma in the form of his preceding film, Viridiana (1961) which despite its selection at the Cannes Film Festival, was released to much public derision for its supposed profane reconstruction of the Last Supper. Despite this public attack, his producer and husband to actress Silvia Pinal, Gustavo Alatriste, granted Buñuel full creative freedom with The Exterminating Angel.

For a filmmaker with an orientation toward the abstract and the surreal and with total belief in cinema’s ability to manipulate—for whom the anodyne and “base stories” of Hollywood are a waste of resources—I wonder if this presence of the boom mic or the overall countervailing style displayed in this film, isn’t Buñuel’s deliberate exhibition of his newly achieved artistic freedom. A confidence in his ability to implant these little fragments, these distortions and non sequiturs; the boom mic, his directorial hubris on display, as if to say, “here is the filmmaker, do you see me?” Perhaps it is in response to this bout with censorship that Buñuel felt compelled to reassert the surrealist tendencies of his earlier films, (Un chien andalou, L’Age d’or, for example).

Again in The Cinema, Instrument of Poetry, Buñuel clarifies his propensity for the experimental by saying “In cinema, images appear and disappear through dissolves and fade-outs; time and space become flexible, shrinking and expanding at will; chronological order and relative lengths of time no longer correspond to reality; and actions come full circle, whether they take a few minutes or several centuries...” (15). Indeed in The Exterminating Angel, there is a sense that this cycle of entrapment could be repeated ad infinitum, with each new institution on display falling subject to a similar treatment. And in the film, Buñuel demonstrates this notion of cinema’s flexibility—what Walter Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility would later describe as cinema’s inherent ability to target the emotional realm— through his use of major ellipses and strange repetition of shots. Along with these devices, Buñuel uses double exposure to elucidate the affective states of the guests, parallel narration to create a dramatic tension between those on the outside of the mansion and the guests inside, and stop motion animation to effectuate the etheriality of the disembodied hand in one guest’s late hour hallucination. In this film, Buñuel is proving his theory of cinema’s capacity to be more than simple pictures within a simple narrative.

However, it is not as if Buñuel is unaware of or unable to use the devices of institutional cinema of the time. In fact, in the film’s penultimate scene and final moment in the mansion’s living room, Buñuel involves familiar dramaturgical techniques from the Hollywood films he assails, along with his own approach, to manufacture an altogether subversive experience for the audience. Just before Nobile has committed to killing himself at the group’s behest, Leticia has an epiphany, albeit an arbitrarily motivated one. Framed under the molding near to the grand piano, she breaks the silence with an adjuring monologue, her arms open to the nearby Doctor Conde (Augusto Benedico), who becomes an advocate for the group’s cooperation. Enfolded by the haggered guests, the master-take floats to a wide in a steady tracking shot that follows her slow but frantic amble about the salon.

Finally, after a cut into her close up, Leticia reveals, “...people and furniture—are exactly where we were that night? Or am I hallucinating again?” As it turns out, after days of moving about the single room, unable to leave, each person, albeit sallow and in two cases deceased, is in the position within the room when they first noticed that they weren’t able to leave. A few characters affirm Leticia’s suspicion in a series of singles that energize the editorial pace. Here Buñuel is finally using some familiar filmic tendencies to telegraph a hopeful tone for the audience, with the hostess like the heroic detective in a crime story, leading to conclusion. Then, Leticia hurriedly moves to Blanca (Patricia de Morelos) who is resting in a dejected slouch on the piano’s lid. In the two-shot, Leticia urges her to play the sonata by Paradisi once again. Finally, in a crash zoom into Leticia’s desperate expression, she urges, “Just the ending. Nothing more. Do you hear me? Play it.” This dramatic single of the beautiful and muliebral Pinal is in every way redolent of the Hollywood lead actress taking her close up.

Now, with the lilt of the sonata’s close, Gabriel Figeroa’s fluid camera sweeps across the room of static guests apparently unmoved by the performance; fixtures resting like a tableau vivant not dissimilar to the sculptures and paintings which surround them. The song concludes and Leticia sustains her conviction, begging the group to “Remember. You must remember.” Falling prey to the same mannered etiquette by which they were originally cannibalized, one guest depressively wrapped in a linen sheet, shakes Blanca’s hand and compliments her with a vacant stare, “a delightful performance.” “Pity there was no harpsichord,” echoes Nobile, the group now finding motivation in this familiar mode. Blanca declines the invitation to play some Scarlatti and suddenly there is a collective sense that the spell has broken. The group exclaims in resounding bliss, scrambling now as Leticia guides them through the threshold behind which they were trapped. One final high angle wide shot shows the guests scurrying through the doorway like harried mice in a lab experiment.

It isn’t until this moment, ten minutes before the film’s conclusion, that any audience member might contact any sense of satisfaction in the way of comprehending the circumstances of the protagonists. However, despite this moment’s container of sincerity, the solution remains a nonsensical directorial construction; one as arbitrary as anything else in the film. In this way, Buñuel is borrowing from the classical mode through the feeling of the epiphany without offering any actual understanding. The dramatic performance, the low angle framing, the eventual fast cutting, all telegraph the feeling of resolution and therefore satisfaction, but it is ultimately a false and a deeply sarcastic one. In this sense, the joke is not only on the nobility, but on any audience member who falls prey to this familiar cinematic manipulation.

It seems that for Buñuel, as was the case for many of the Surrealists, (though Buñuel is of course, not limited to this container), that there is a morality attached to style. As the artist states in a Film Quarterly essay from 1967, “Surrealism taught me that life has a moral meaning that man cannot ignore. Through surrealism I discovered for the first time that man is not free. I used to believe man’s freedom was unlimited, but in surrealism I saw a discipline to be followed. It was one of the great lessons of my life, a marvelous, poetic step forward.” (Harcourt 3)

It is through this insincerity and this distance from any saccharine emotionality that Buñuel is able to transcend the institutional mode. In a February 1969 New Yorker article, Pauleen Kael described Buñuel’s style as being “pleasurably ironic” in the “cool distance” he keeps from the audience—always in avoidance of sentimentality. She posits something new in relation to his art being strictly a critique of those within the projected image. “To be blind to Buñuel’s meanings as a way of being open to “art” is a variant on the very sentimentality that he satirizes. The moviegoers apply the same piousness to art that his mock saints do to humanity.” To this end, Kael expands the diameter of Buñuel’s criticism to include the audience, which I think is happening with much acerbic clarity in this false denouement at the end of The Exterminating Angel.

While the primary target of scrutiny in this film is clearly the aristocracy—which some might argue stands as a proxy for the Franco era elite to which Buñuel was deeply opposed—this is not to suggest that Buñuel’s perspective is exclusively anti high society or anti middle class. Rather, in so far as he points the camera to the audience as well, the film is anti institutional. As Kael posits, no one is in fact safe from Buñuel’s cutting vituperation. Though Buñuel does offer the audience a psychological buffer zone by supplanting the story onto the clowns of the upper class, it seems clear that his ultimate position, especially in this provocation of the audience, is that any faction of humanity can be complicit in institutional norms.

It is Buñuel himself who argues for the universal critique of society. In his interview with Jose de La Colina and Tomas Perez Turrent in Object of Desire, “I believe that what happens to Nobile’s guests is totally independent of the social class to which they belong. With workers or peasants, something very similar would happen, but in a slightly different form. Aggressive behavior isn’t exclusively bourgeois or exclusively proletarian. It is innate to the human condition, even though a few, only a few, psychologists or anthropologists deny this. While a worker may his his wife, someone from the middle or upper-middle class might prefer to torture her psychologically. That’s why I say that if it had happened among workers, the drama in The Exterminating Angel would be weaker, less interesting; that is why, instead there is more contrast between the exquisite forms of Nobile’s guests and the almost bestial state to which they finally succumb.” (162)

Put into conversation with Randall Conrad’s Cineaste article from 1976, A Magnificent and Dangerous Weapon: The Politics of Luis Buñuel’s Later Films, we can develop an understanding of Buñuel as an artist with contempt or at least frustration with all institutions of society. Here Conrad posits the following with reference to Buñuel earlier breakthrough and masterwork, Los olvidados. “By the same token, however, Los olvidados is by no means a politically encouraging work. The poor are amoral and vicious, and every character is the plaything of destructive forces as inescapable as destiny in ancient tragedy…” (11).

Though Buñuel does push the group toward what most would consider to be the limits of depravity, with some guests relieving themselves in china closets and others anarchically demanding the death of Nobile in a bout of collective frustration, in a later interview, Buñuel admits to some regret for not having pushed the dramatic choices into greater debasement, e.g. canibalism or murder. This self-censorship notwithstanding, one idea does emerge from this narrative choice to free the group through their repetition of experience. There is a direct line between these institutions as containers for experience and their tendencies to habituate behavior. Observing this within the precarious post war atmosphere, the film could be interpreted as warning to the global military complex of the time.

Or is this breaking free of the institutional entrapment more related to Buñuel’s identity as a Spanish emigre making films in Mexico? The immigrant experience is something like a container itself, a vacuum—with Buñuel’s at least often feeling tenuous. I am thinking here of his experience in America and the retraction of his opportunity for citizenship over his supposed leftist political leanings (Kinder). At its core, The Exterminating Angel is continuously putting the notion of boundaries on display and the expectations that certain groups hold over others. At one moment, just after one of the guests realizes that they’ve run out of water, and an elegiac sense of hopelessness starts to penetrate much of the room, another guest responds to the fact that no one has come for them with, “The attitude of those outside concerns me more than our situation [in here].” (25) There is a transference taking place between Mexico and Spain with consideration to Buñuel’s depictions of each country in various films. As elucidated in Marina Perez de Mendiola’s Buñuel’s Mexico, Sauro’s Tango: An Act of Reterritorialization, his act of “a postmodern nomadism” (32) denies any attempt that critics have suggested of films like Los olvidados as being anti Mexican or an inaccurate depiction of urban life.

Or is this notion of institutional entrapment not more related to the history of the Mexican studio system and its perpetual tethering to Hollywood? Is Buñuel pointing instead to the storied history of Mexican film, with this, his final picture in the country? For decades, the Mexican studio system experienced a series of crises in its attempts to evade or mimic the hegemony of the Hollywood model, at times often jostled into new forms replicating even the imperialist tendencies of other western influences vis a vis Latin America, all based on global political needs. And through the decades of the so-called Golden Era of the Mexican studio system, were filmmakers not entrapped by the imperative to establish some sort of Mexicaness in film?

I wonder about The Exterminating Angel’s message about the dangers of repeating history most of all. A warning to institutional dependencies everywhere. Is this film not a satirical cry against these powers like the church, like fascistic complicity, like our collective proclivity toward cruelty? We, (the audience), don’t mind laughing at the elite because there is an emotional distance between us. But I wonder how the film would affect if we could place images of ourselves in the mise en scene. In Karl Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, he famously cites Hegel by saying that history repeats “first as tragedy, then as farce.” No doubt concerned with history’s tendency toward repetition, in his autobiography, Buñuel mentions that the worst thing about death is that he won’t be able to read tomorrow’s newspaper. With this concentration on the past, it is as if in The Exterminating Angel, Buñuel is begging us to “Remember. You must remember.”

WORK CITED

Backstein, Karen. Cinéaste, vol. 34, no. 4, 2009, pp. 56–58. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41690830. Accessed 1 Jul. 2022.

BENJAMIN, WALTER, and MICHAEL W. JENNINGS. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility [First Version].” Grey Room, no. 39, 2010, pp. 11–38. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27809424. Accessed 1 Jul. 2022.

Estève, M. (1978). The Exterminating Angel: No Exit from the Human Condition. In J. Mellen (Ed.), The World of Luis Buñuel (pp. 244–54). New York: Oxford University Press. Google Scholar

Conrad, Randall. “‘A MAGNIFICENT AND DANGEROUS WEAPON’: THE POLITICS OF LUIS Buñuel’S LATER FILMS.” Cinéaste, vol. 7, no. 4, 1976, pp. 10–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42683242. Accessed 29 Jun. 2022.

Harcourt, Peter. “Luis Buñuel: Spaniard and Surrealist.” Film Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 3, 1967, pp. 2–19. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1210106. Accessed 30 Jun. 2022.

“The Exterminating Angel.” Harvard Film Archive, https://harvardfilmarchive.org/calendar/the-exterminating-angel-2000-12.

de Mendiola, Marina Pérez. “Buñuel’s Mexico, Saura’s Tango: An Act of Reterritorialization.” Chasqui, vol. 35, 2006, pp. 26–45. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/29742147. Accessed 20 Jun. 2022.

Buñuel Luis, et al. “20: El Angel Exterminador.” Objects of Desire: Conversations with Luis Buñuel, Marsilio, New York, 1994.

Buñuel Luis, “The Cinema, Instrument of Poetry.” Cuadernos de la Universidad de Mexico (Mexico City) J. Francisco Aranda, Luis Buñuel. Biografia critica., 1958.

Kael Pauleen, “Saintliness.” The New Yorker. 109 February 7, 1969