OVER AGAIN: THE DEBRIS OF EXPERIENCE

Reflected back into life is our own compulsive capturing of it. At every turn, it seems that our lives are being recorded and our impulse to commit moments to data has reached, what feels like, an automatic apex. Indeed, our experiences—our lives—are surveilled, scanned and logged chronically. These recordings can speak different languages—memorial, procedural, self-expressive—but all contend with excess. Our phones, at intervals designed to encourage more recording, push us grand and personal montages of not so distant life moments. They feed them to us and say, remember who you were at this place, two years ago, as if to threaten some future possibility in which we might not recall. Corporations chart our interests, images and habits. They program clandestine marketing and algorithms to sell our own experiences back to us. The state uses our possessions to surveil: traffic lights capture the letter and number sets on our license plates and mail us evidence of our transgressions. We receive grainy aerial images of ourselves surrounded by language in codes that tells us about ourselves on some day prior. All of this banal context—images, experiences and bits of language—the excesses of our era of compulsive content capture, is stored in data centers that are fueled in ways—nuclear and coal—that are economically and environmentally costly. It is an increasingly absurd and relentless project of record keeping that softly atrophies our ability to perceive.

However, a number of artists and writers, particularly those working in the expanded field, have attempted to organize the debris of experience through poetic means. The traffic violation letter is not an inherently poetic artifact, the same way a storefront sign or impromptu selfie is not. These items and these experiences are rarely brought to us in an artistic context. They are pushed. Manufactured either thoughtlessly, compulsively or with some commercial utility in mind. Perhaps because of this, or owing to their profusion, they become the bits of life that we disregard or forget about entirely. Indeed, in this context of gross information, more moments are consciously abandoned than are remembered. As Walter Benjamin would say in his hinting toward the crisis of meaning in the modern era, “that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of a work of art,” (The Work of Art in… 221). Here Benjamin argues toward a loss of potency in the experience of art as it is reproduced—as it is experienced virtually.

But for these artists, it is precisely this mundane or commonly discarded recorded matter that becomes a sort of poetic material. These are artists who embrace the Benjaminian counter perspective of reproduction holding an emancipatory potential for art, (224). In her photographic and poetic work, Memory, for instance, Bernadette Mayer developed a way of organizing the banal events of a single month through text and image in a way that became both programmatic and fluid, deeply personal yet removed in its abstraction. Hollis Frampton, in his work, Zorns Lemma, arranged familiar material from the world around him to almost mathematical effect, resulting in a limit case for art’s potential to be self expressive. And in Christian Marclay’s The Clock, a sense of the universal emerges through the obliteration of subjectivity as he organized recorded material to meditate on time. All of these works create a record less in service to memory as much as a structuring of our experience under the modern condition of excess.

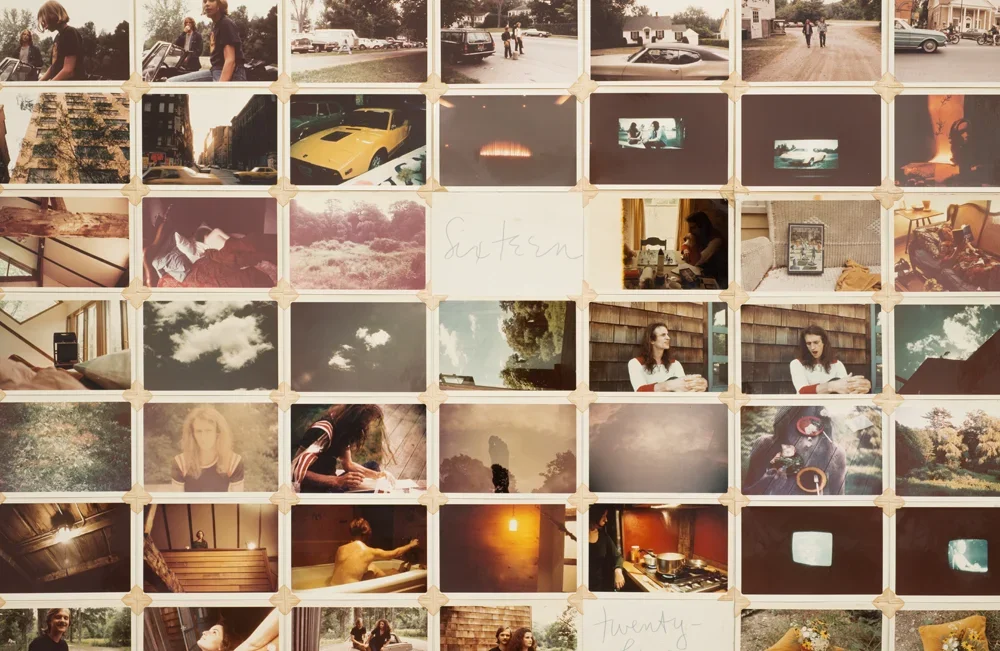

In each of these pieces, there is a system of formalistic constraints for dealing with accumulation, often to the emergence of a unique poetic language. In Memory, Bernadette Mayer organizes one month of her life—July, 1971—through images and stream of consciousness text which she recorded as six hours of audio for the work’s initial physical exhibition. In what is a simple program: expose one roll of slide film each day and keep a written journal, she comes into contact with the boundaries and perhaps purpose of manual recitation. Rather than record with motion film and continuous audio, the 35mm roll forces her to edit the occurrences of a single day to thirty-six instances.

Indeed, of the over one thousand images which comprise the month of July, what becomes noticeable is that which is occluded. That is to say, despite the excess, there is still absence. Here, Mayer makes obvious what is the fundamental “trick” of photography: that it is both objectively true and subjectively manipulative, or as Susan Sontag in On Photography writes, “The conflict of interest between objectivity and subjectivity, between demonstration and supposition, is unresolvable. While the authority of a photograph will always depend on the relation to a subject (that it is a photograph of something), all claims on behalf of photography as art must emphasize the subjectivity of seeing” (Sontag 106). Because more of the world exists beyond the frame lines of an exposure, a photograph is an inherently manipulative artifact. But Mayer goes on to clarify her thoughts with, “It’s astonishing to me that there is so much in Memory, yet so much that is left out: emotions, thoughts, sex, the relationship between poetry and light, storytelling, walking…” (Mayer 7). Mayer’s point reveals some truth in the actual function of memory as well: that the sensational is often what is preserved more so than the ordinary. I wonder here if Mayer is attempting to override the conventional function of memory with her inversion of our relationship between the quotidian and the grand. Scanning through the book, one notices simply what Mayers was noticing across the month of July. Ceilings with provincial light fixtures, chairs in the corners of rooms, the blur of lights at night, amber rooms underexposed from the available light in some rural cabin, treelines reflected into windshields. One can recognize the moments, where scattered between her attention toward the inanimate, people become the photographic objects of her preoccupation. These tender portraits often feel less like formal or classical psychological studies of another, as much as the material record of her passing gaze. It is a blur of life. In his analysis of Ron Siliman’s prose poem, Sitting Up, Standing, Taking Steps, Andrew Epstein describes the work, which is a mostly direct recording of the experiences of the artist’s day, as “defiantly untransformed, neither aestheticized nor turned into metaphor or symbol. The passage does not seem to be ‘about’ anything, either, other than the day itself in all its dailiness,” (Attention Equals Life 198). I think there is a relationship with this analysis of Silliman to what Mayer is attempting to do with her photos.The exhibition view furthers this impression. The thirty-six feet of images, provides a zoomed out portrayal of the whole experiment and a moving impression of life in a single month. With this scale it is easy to bear witness to the enormity of experience contained in any one life and how easily the universal (time) can live alongside the intimate (the moment).

Mayer opens the book, July 1, with “& the main thing is we begin with a white sink a whole new language is a temptation (9).” She starts in media res and allows the sentence to drift into incoherence. She begins as if to make an irrefutable declaration of time’s omnipresence and of consciousness as something that had, heretofore already existed; that there was life and its constituent moments before July 1. The stream of consciousness style prose poetry that in the book form, (mostly) mirrors the presentation of the grids of images, also offers glimpses into the occurrences of July, however there is a distancing effect in its abstraction. But this approach, while being reflective perhaps of the state of being in memory or consciousness, also expands upon this idea that time is absent of a terminus. While everything in the book and even the exhibition is presented in a tidy grid, present too, is a sense of diffusion and continuity. With effort, one is able to hang onto the small bits that cohere and admire her notions of familiar reality. The image of the white sink that leads the series is symbolic of Mayer’s dealing with the mundane through photographic means. It feels more reverent than tolerant and recalls the practice of Moyra Davey, in her work, Index Cards, where she reveals a friend’s understanding of cooking to be “about managing his fridge,” (1). Indeed, much of Memory seems to be about managing the excesses of time and mundanity. As in, “back windows across the street i’m in sun…(9).” Instances like these compare to images in her grid, though the precise coordination requires close reading. On page twelve, the second image on the roll is of Mayer herself, “in sun,” holding her camera. But perhaps this line relates more to the seventh image of someone who might also be Mayer, sitting against what could be the “back windows,” (9) in the sun. In this way, her words evoke feelings which the images activate and vice versa. The work presents a way of dealing with time and the experience of memory. Less teleological than evocative. Through her formal constraint she is able to locate some form of recording which is both instructive and impressionistic. It seems the project of Memory is not to telegraph the experiences of every moment of life from July, but rather to order some of them and perhaps acknowledge the ones that would ordinarily disintegrate.

In Marclay’s The Clock, there is a similar sense of constancy that Mayer’s work acknowledges. However, while Mayer relies on the balance of extemporaneity and rigor to create an evocation of time and memory, Marclay uses the interplay of various film recordings of time to meditate on our relationship with it. It is a piece that synchronizes roughly twelve thousand of the in-between moments from film media which reference time, or in which a clock is shown, to the viewer’s real-time and over twenty-four hours. Marclay uses match cuts and the compilation of thematically similar moments to drive forward a lyrical, almost hypnotic masterwork of film. It is another way of dealing with the excess of experience to poetic effect.

In his use of popular culture and the cutting together of repeated musing toward time, Marclay’s proves how our relationship to time has become mythologized. A clear and inescapable subjugation with respect to time is at the forefront of the piece, bringing to mind Guy Debord’s notion that, “Time, as Hegel showed, is the necessary alienation, the environment where the subject realizes himself by losing himself, where he becomes other in order to become truly himself,” (Society 161). Indeed, underneath the shimmering appeal of familiar media icons is a mortality salience that rests between our experiences and time itself. There is a sense of dissociation present in this work and especially in its fractured form. Time seems to dilate under the condition of its own awareness and drift between presentness and disappearance. At certain points in the viewing, time felt as though it were flying by and others, dragging on. I found myself attempting to deny the presence of time any moment a thought of obligation outside of the screening room appeared in my consciousness. Perhaps this too is at the core of Marclay’s project: the attachment of time to consciousness and our attempted rejection of it. There are many instances where objects are strewn into clocks, bullets are fired and men hurl various timekeepers dramatically across sets—a declaration of our frustration and our attempts to intervene with time’s omnipotence. Martin LaSalle as Michel from Bresson’s Pickpocket stealthily unravels a wristwatch from a chair leg, (his practice), as a way to steal time. In Hook, the eponymous villain delights, “ahh,” at the malfunction of a room of “broken clocks.” These moments, in isolation, outside of the context of their usual narratives become instead reflections on the universal perspectives toward time. Not only do the metaphors become obvious in this form, but in drawing forth the grand drama of our relationship with time, Marlcay also reveals the basis of its ontology. Charlie Sheen stares into a mirror fixing his tie in Wall Street, and offers a platitude which is perhaps at the locus of this project’s mission with “well, life all comes down to a few moments. This is one of them.”

The Clock, through its insistent decontextualization illustrates the fractured nature of memory through these moments. Viewers of The Clock, like viewers of Memory, can enter into the piece at any point in the work’s progression. With this superstructure of time and the absence of clear story, the work sacrifices subjectivity in service of a larger attempt to articulate the ubiquity, and perhaps repetitiveness, of our experiences. While Debord’s preoccupation with time in this passage is oriented toward labor relations, the perspective still applies: “The natural bias of time becomes human and social by existing for man. The restricted condition of human practice, labor at various stages, and as separate irreversible time of economic production” (Society of the Spectacle, 163). On the one hand, The Clock depicts time as the universal manager of our experiences. However, the discrepancy which Debord elucidates is also on display in Marclay’s work. Quasimodo swings from a bell tower in glee as the film and the day reaches twelve, noon, while conversely, Mlle. de Poitiers in Picnic at Hanging Rock, (1975), addresses Miranda with, “your pretty little diamond watch?” She replies, “Don't wear it anymore. Can't stand the ticking above my heart.”

In his film, Zorns Lemma, Hollis Frampton’s experimental structure goes beyond the representation of experience or relationship with time, to the modeling of cognitive processing itself. As Wanda Bershen writes of post-1970 experimental cinema more broadly, “A primary concern was the recognition of how central the preconscious and irrational level of experience is to all human behavior. Like poetry, these films attempted to appeal directly, by means of potent imagery and rhythmic structure, to our emotions,” (Bershen). Frampton’s work attends to this impulse through a rigid system of substitution, duration and associative pairings. As Bershan alludes, one can draw a parallel to modernist poets—and here I extend— like Gertrude Stein whose poetic systems also dealt with substitution and the insistence of motifs as a way to describe a continuous present, (Kirsch, 77). Similar to The Clock, Frampton evokes the sense of the continual through a lyrical and constant montage of images. Rather than glamorous movie stars, his pedestrian “letter words,” followed by “letter images” and simply, pictures of letters themselves constitute the cinematic material. These words are initially found in urban environments, (storefronts, urban wayfinding, advertisements) and in each case represent the viewer’s place within the alphabet, indicated by the first letter. New words appear successively, however, in each round, letters are gradually replaced by purely imagistic depictions of moments, these, in new contexts to ultimately create a tension between the urban and the pastoral. These substitutions occur rapidly and their meaning is kept in abeyance until the end, where the film becomes a montage of these substituted images. Even still, their direct meaning is unclear. This middle section follows an opening that too uses the constraint of the alphabet, effectively introducing the program through voiceover and a succession of fluttering metal letters on black.

Frampton relies on pattern and repetition to create a viewing experience that is cumulative and dense. It relates, somehow, to the experience of being within information and to the subconscious process of codifying the many visual cues around us in life. There is a lyricism in his work, albeit a languid and hypnotic one. It refuses the typical arc of storytelling or even the subjective impressionism of Memory. It is however a durational experience that sits somewhere within order and randomness and relates, I think, to Wallace Steven’s claim of Stein’s work, where words are, “less used for their referential qualities and more for the spaces they can create in a theatrically artificial and temporary juxtaposition” (The Performance of Modern Consciousness 44). I wonder here if Frampton shared this understanding of language having a spatial quality—that it occupies the physical world and creates space. At the end of the film, there is a religious voiceover set to a dull metronome, each word uttered like the preceding clips—one at a time—and an image of two people becoming increasingly diminutive in the frame across a field of snow. Visually, this feels like a respite to the overloaded montage from sections one and two. Bersham in the same article suggests this to be some universal resignation to the “incommunicable” aspect of knowledge, but I’m not sure I see the preceding film in the same didactic manner. Through Frampton’s matrix of 24 FPS footage against the twenty-four letters of the alphabet, I instead see a corollary around dealing with time and perhaps more broadly, existence. Like The Clock and like Memory, this piece positions a formal constraint against the maximalism of information to generate some understanding of our experience.

What is interesting is the way that the piece’s structural minimalism is complicated in the context of accumulation. Frampton’s form is straightforward when broken down, yet organized in this way, it becomes a sort of maximal text. The machine-like effect of processing information becomes the film’s actual Zorn’s Lemma, or result within the mathematical branch of set theory. Invoking this principle, Frampton suggests that to deal with the surplus of experience, one must rely on progressive substitution. Interesting too that the banal morphs into the sensational, proving Kuleshov’s principle of the relational power of two clips in proximity. In the film bits of seemingly random matter can suddenly appear profound as in, “KE EP LADY MADONNA” (3:42), or “CANCER ECONOMY FALL” (5:38). Like experience, Zorns Lemma is fragmentary and constituted by the fluttering of information. As in real life, one might latch onto patterns of experience or simply endure.

Frampton’s piece reminds me the most of the traffic violation letter. He extracts glimpses from the mechanical, urban world and filters them through the basis of communication. And then, in moving from urbanity to the pastoral in the way the film does, he makes a suggestion toward the mediation of this experience through technology and modernization, such that the bucolic final scene becomes divine. Scott McDonald, in his book, The Garden in the Machine…, acknowledges this ending as a spiritual departure from the “grid” of urban life. However, he goes on to observe the mathematical precision with which Frampton purportedly designed this final section. “That Frampton’s spiritual appreciation of the countryside was motivated by the exhausting rigors of city life seems implicit in his decision to have the Grosseteste text read, one word at a time, by six women, during the majority of the final section. Indeed, the distracting quality of the reading is a means of suggesting that, once the individual intellect has escaped early fears and has developed within an urbanized cultural system, the rhythms of this system are virtually impossible to escape: we can only long for a return to innocence, to the Garden. Or, to return to the final section of Zorns Lemma, we can only see a pastoral vision within the rhythm of language our culture has taught us,” (McDonald 255). While embedded in code, with multiple viewings, this work perhaps does provide a syntax for understanding.

In her work, In Memory of Memory, Maria Stepanova deals with trauma through an intellectual investigation of memory. In it she outlines, “memory is personal; history dreams of objectivity; …that the landscape is strewn with projections, fantasies, and misrepresentations,” (80). Here she also talks about “postmemory,” as the sort of raw material which can be used for editing the past. Her work by and large refers to the fallacy of memory as a faithful record of life’s experiences and the “catastrophe” of bias. To Stepanova, memory and our feelings toward it is a teleological phenomenon. Since memory is an act of recording, albeit flawed, all of these works deal with the notion of the record to the effect of generating new poetic languages. Indeed, as Stepanova says, “Like language, like photography, postmemory is far more than its obvious function. It doesn’t just show us the past, but changes the present, because the past is the key to everything that occurs in the daily present,” (In Memory of Memory 79).

All of these works deal with the intersection of language and photography (or film). They combine image and text in ways that refer to the nature of recording as an experiential or personal act, resisting surveillance or “pure” documentation. Here I am thinking of the filmmaker Jean Renoir who said, “All technical refinements discourage me. Perfect photography, larger screens, hi-fi sound, all make it possible for mediocrities slavishly to reproduce nature; and this reproduction bores me. What interests me is the interpretation of life by an artist” (My Life and My Films Attributed). To this extent, I think these works are as much about memory as they are about recording. If memory is our way of processing the experiences of excess, then indeed these films tolerate experience as a memorial act.

When one thinks about memory, one must also think about forgetting. Here I am again referring to Stein and her notion of repetition as insistence and forgetting as having its own sort of articulation. In Many, Many Women, from 1933, Stein wrote, “She is forgetting anything. This is not a disturbing thing, this is not a distressing thing, this is not an important thing. She is forgetting anything and she is remembering that thing, she is remembering that she is forgetting anything.” I think Stein makes the claim that these other works illustrate as well: that forgetting creates structure.

Much of what these works contend with is saturation—data, language, experience—and explore the limits of what can be recorded, remembered and transmitted. They provide theoretical, mathematical and self expressive responses to the philosophical dilemmas of experience, considering the banal as their primary material. They look at the everyday, the in-between moments and our relationship with time, as more than background information, but as the basis for an artistic syntax which can tolerate and at times decode the womb of excess around us. For Paul Celan, poetry can serve as a sort of mediation tool for experience. In his Speech on the Occasion of Receiving the Literature Prize of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, Celan says that, “For the poem does not stand outside time. True, it claims the infinite and tries to reach across time - but across, not above.” Like all of these works, the poetry does not exist outside of time, but within our relationship to it.

However, not all experience can be ordered. After all, there is chaos and peril. Things, like the Holocaust for Celan, cannot be explained, much less put into structure. Later in the speech he says, “Toward what? Toward something open, inhabitable, an approachable you, perhaps, an approachable reality. Such realities are, I think, at stake in a poem. I also believe that this kind of thinking accompanies not only my own efforts, but those of other, younger poets. Efforts of those who, with man-made stars flying overhead, unsheltered even by the traditional tent of the sky, exposed in an unsuspected, terrifying way, carry their existence into language, racked by reality and in search of it.” Here Celan acknowledges the limits of language’s ability to mediate certain experiences. He thought of trauma as something nearly incommunicable. In the introduction to Poems of Paul Celan, xxix, his translator, Michael Hamburger wrote, “What is certain is that he both loved and mistrusted words to a degree that has to do with his anomalous position as a poet born in a German-speaking enclave that had been destroyed by Germans. His German could not and must not be the German of his destroyers. That is one reason why he had to make a new language for himself, a language at once probing and groping, critical and innovative.” Celan’s poetry does not resolve the dilemmas that these artists contend with—that we are saturated by experiences and surrounded by time—but it does reveal the point at which poetic systems, regardless of their rigor or tenderness, reach their impotent conclusion. His perspective determines the failures, not of this kind of art, but more broadly, the limits of language’s ability to fully contain experience. While artists like Mayer, Marclay and Frampton can make form out of debris—manage the contents of the fridge—Celan suggests that some experience remains unfilterable.

WORK CITED

Epstein, Andrew, Attention Equals Life: The Pursuit of the Everyday in Contemporary Poetry and Culture (New York, 2016; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 June 2016), https://doi-org.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199972128.001.0001, accessed 1 May 2025.

Renoir, Jean. My Life and My Films. Translated by Norman Denny, Da Capo Press, 1991.

Sharon J. Kirsch. Gertrude Stein and the Reinvention of Rhetoric. University Alabama Press, 2014. EBSCOhost, .

Sara J. Ford. Gertrude Stein and Wallace Stevens : The Performance of Modern Consciousness. Routledge, 2002. EBSCOhost, .

Gertrude Stein, “Many Many Women,” in Matisse, Picasso, and Gertrude Stein: With Two Shorter Stories (Mineola, NY: Dover, 2000), 117–198, 119.

Debord, Guy. Society of the Spectacle. Rebel Press, London, 1992.

MacDonald, Scott. The Garden in the Machine: A Field Guide to Independent Films about Place. University of California Press, 2001.

Hamburger, Michael. Introduction. Poems of Paul Celan, translated by Michael Hamburger, Persea Books, 1988, p. Xxix.

Marclay, Christian. The Clock. 2010. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2025. Installation.