Staying with the thing

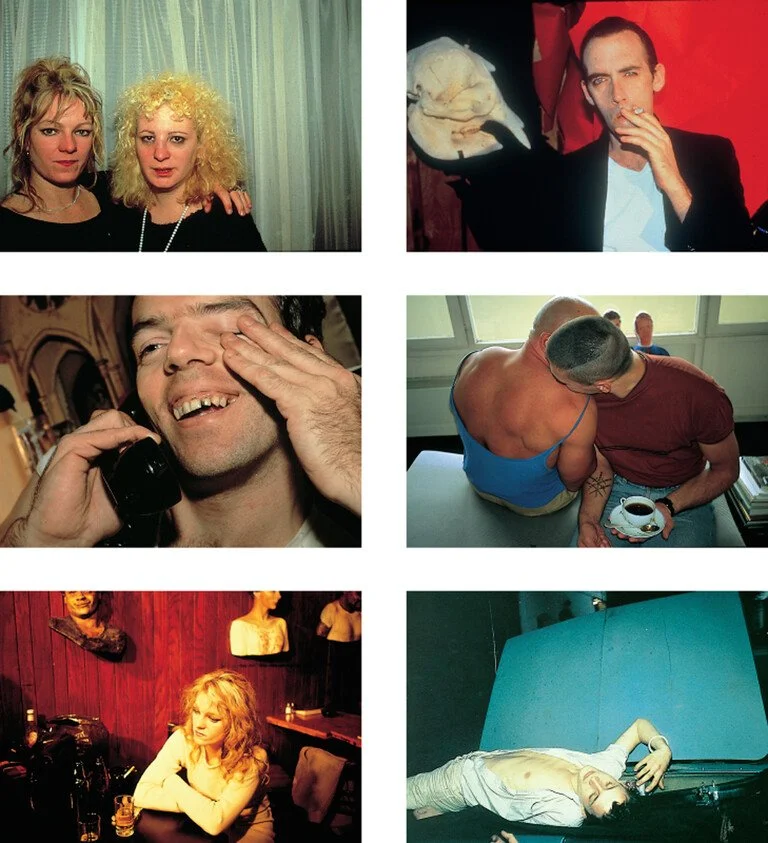

There are projects which are lauded for their diffusion. One thinks of Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency (a truncated version of which I just saw in London this past week), perhaps, Alec Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi, Stephen Shore’s Uncommon Places; anything by Wolfgang Tillmans. These are works which reject the tidy visual construct, opting instead for visual range. Projects like those above are definitionally rigorous but operate simultaneously with a freedom of form. By and large, these works are sociological. They refer to the broad spectrum rather than the single phenomenon. They say, “generally things are like this over here or during this time.” They leverage mood, however seemingly objective or apparently authored, to obviate emotion and create their politics. Of course, the austerity of a Soth portrait does something very different from the luridness of a Goldin interior, while being weighted in some kind of shared sensitivity. While also oriented toward diffusion, Eggleston’s pictures do something different from the above. His command over industrial color and seeming happenstance create a taxonomy of things rather than people exclusively. Perhaps this is because Eggleston gets to the soul of things, be it, in Mississippi, Berlin, California, Mexico and despite his perspective that, “things don’t matter.” Donna Tart, in an Art Forum piece I read years ago said that “things must speak in code to Eggleston (sic).” All to say, it’s in their orientation toward variety that some fundamental premise about a place or a group of people becomes manifest.

Indeed, I looked at a wide range of compositions in the Goldin show at Gagosian. Her snapshots seemed only to be linked by the sense of intimacy that defines her work. Otherwise, standing back from the three walls, the tapestry of color and out of focus awkwardness all served to reflect the diversity of her friend group during these years. They carried a sense of liberation that was pure feeling and pure rejection of any self-imposed rule or institutional regulation. Whether people or things, the above artists use diffusion to their advantage to create the visual tapestries, as prime example, like the Goldin work that shimmered for me on Davies Street. However, this is just one approach to the cataloging of ideas; one avenue toward using images to make a political statement.

Increasingly, our visual world is ordered around this sort of endless variation. However, there is something alluring to its symmetrical counterapproach. By contrast to the above works, there are those which rely on repetition of a single experience to accumulate meaning. Whereas one can look at a single Goldin and wonder if that person’s life was cut short by disease, if they are one of the many poets or artists whose life her camera knowingly and necessarily memorialized, these works are more durational. Often described as rigorous—an analogue for minimal—in their visual form, these projects expose larger happenings through a narrow visual field.

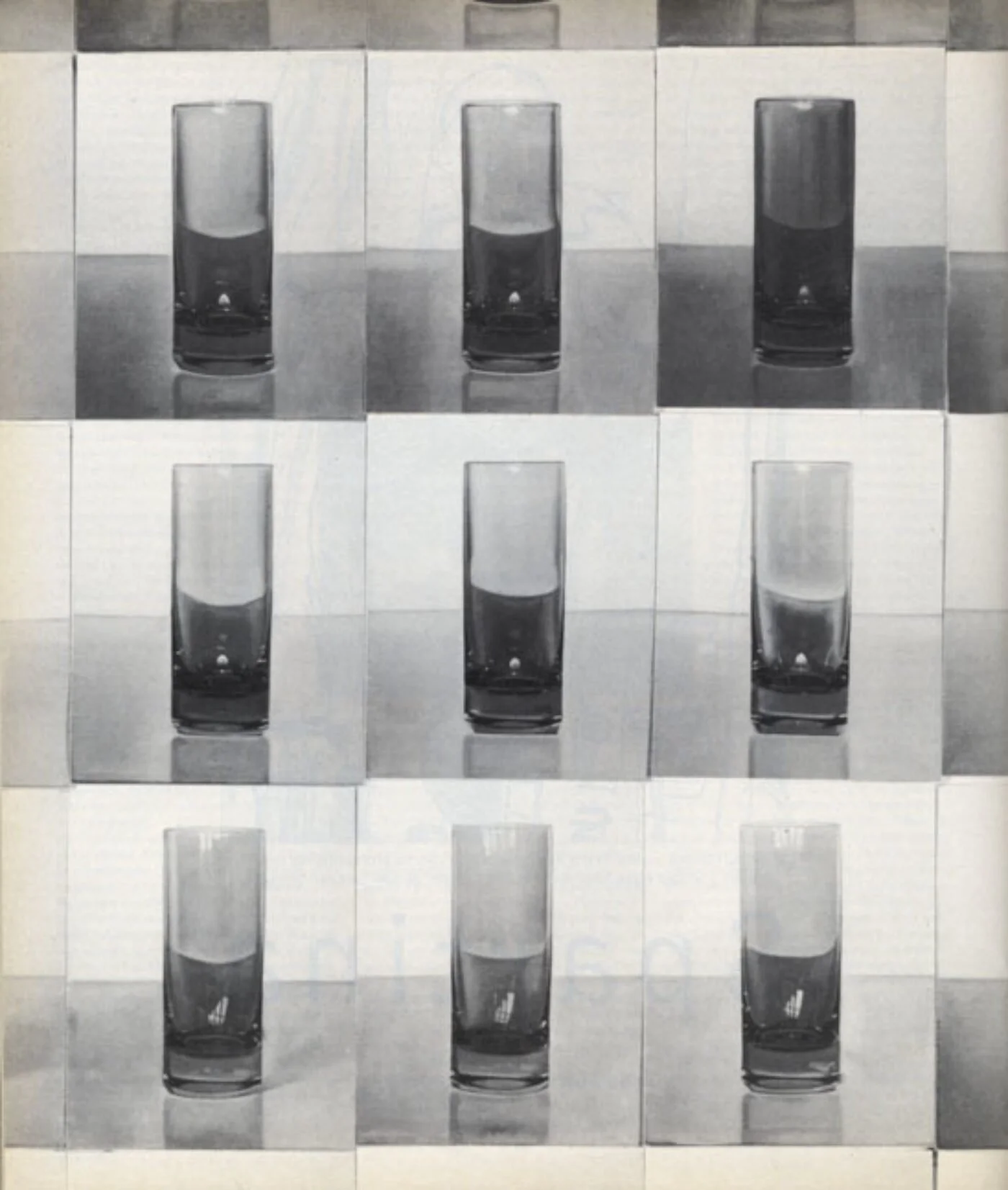

I love both sorts of work but have been thinking lately about the potency of the latter, especially, perhaps, as a palliative to the constant visual diversity I surround myself with. I like that through a clear visual focus, subjectivity can take on new meaning. This interest started with Peter Dreher’s water glass—which I have written about before—an object which is of course unremarkable until it is painted, not once, but roughly five thousand times over forty years, wherein it becomes divine. Here, his process of looking is much closer to the Greek originator, theoria, which simply means, looking. Goethe had a similar perspective: that sustained looking could result in an almost scientific, certainly ecstatic understanding of something. The only difference between Goethe and, for example, Newton, is that when Newton looked through the crystal to observe the prism, he was concerned with the way the light refracted, whereas, Goethe was concerned with how he felt when the rainbow hit his eye.1 This is the code that Eggleston understands, or intuits, from the material world around him I think. Certainly what Goldin felt in any room in the Chelsea Hotel. That things and small moments can be ecstatic.

But as Dreher proves, there can be revelation in sameness. In Alejandro Cartegena’s Carpoolers series, the photographer looks, extensively, at passing flat bed trucks in his home town of Monterrey in Mexico. Each image across the four episodes shows the hidden effects of labor—particularly the distance between that labor and municipal infrastructure—as a result of Mexico’s increasing suburban sprawl. In the work, he establishes an obvious visual construct: the aerial perspective of a truck, shot from exactly the same vantage point on an overpass and in relatively the same clarifying light. They often show laborers being transported to or from job sites, napping, talking or simply being for the fleeting moment of exposure. To witness a single image is to be met with an understanding that one already likely has about exploited work forces, whereas in the aggregate, the message is much louder. This project might be as successful were Cartegena to have made portraits of the laborers and followed them, documentary style to their job sites, but not as distinct.

In Dreher’s monumental project that spanned forty years, each painting becomes a record, not only of time and place, but of his particular capitulation to reality, day in and day out. Across the thousands of small 8x10” paintings, one can observe his own relative precision or attention to light and shadow and not just the myriad small changes in environment which one might otherwise regard as completely the same. Structurally, Cartagena’s project is akin to Dreher’s, only the variations within Cartagena's format are more obvious. Often he breaks his tight structure to create a proxy, showing truck beds which aren’t carrying laborers at all, but the artifacts of work: bags of soil, trash, tools. One such spread shows a pile of colorful garbage bags on the verso and a man in yellow on the recto, both flattened as if by g-force pressure.

I like what Dreher attempts to highlight about mundanity in his work. It is the Tender Buttons of the painting world for me; it says something about our dependence on symbols and perhaps that, like language, they are only maintained out of a lack of creativity. When the glass is painted to exhaustion or the word is stated ad infinitum, what do they become? His work uses the idea of structure to say something completely philosophical, whereas the salient claim in Carpoolers is much more political. Interestingly, when workers are shown in this way, over and over again, perhaps the vague symbol of the worker is destroyed, but the premise of their exploitation is exposed in that absence. Cartagena, in his curation, has allowed us to think of these workers being transported into his home town as objects, while Dreher has allowed an object to help us think of ourselves.

Other photographers have followed this format as well. I’m thinking of Michael Wolf’s works like Architecture of Density or Paris Street View which tend to back out of a very specific visual constraint. The calculus of Wolf’s works, while also rigorous, varies slightly. Whereas the glass in Dreher’s studio was placed in the same location, was affected by the same light just as Cartagena's carpoolers were shot from the same vantage point, relative to him, Wolf inverts the logic of the visual container by making something site dependent. The net effect is a series of images, as in Architecture of Density, which are geographically diffuse, while being visually contained. In his Street View series, however, where he makes images of Google Street View scenes across various places, there is a definite expansiveness that is in tension with the visual containment. Because he is able to move throughout a city, virtually, it takes on an Eggleston-like awareness of place: intimate, but also broad.

In Carpoolers, Dreher’s Tag Um Tag Ist Guter Tag and Wolf’s projects, there is a clear subjectivity in play. However, that authorship is in tension with the feeling of surveillance, especially in Wolf’s works. What I like about all of them is the ways in which they avoid sentimentality. These projects, while emotional in their own way, opt against sensationalising the experiences they aim to capture. They stick with the thing in a way that allows the inevitable deviations to emerge from the sameness. And in their accumulation of like episodes, a different kind of message emerges; new meaning in the destruction of supposition. Indeed, the idea is about ideas and not entertainment, necessarily.

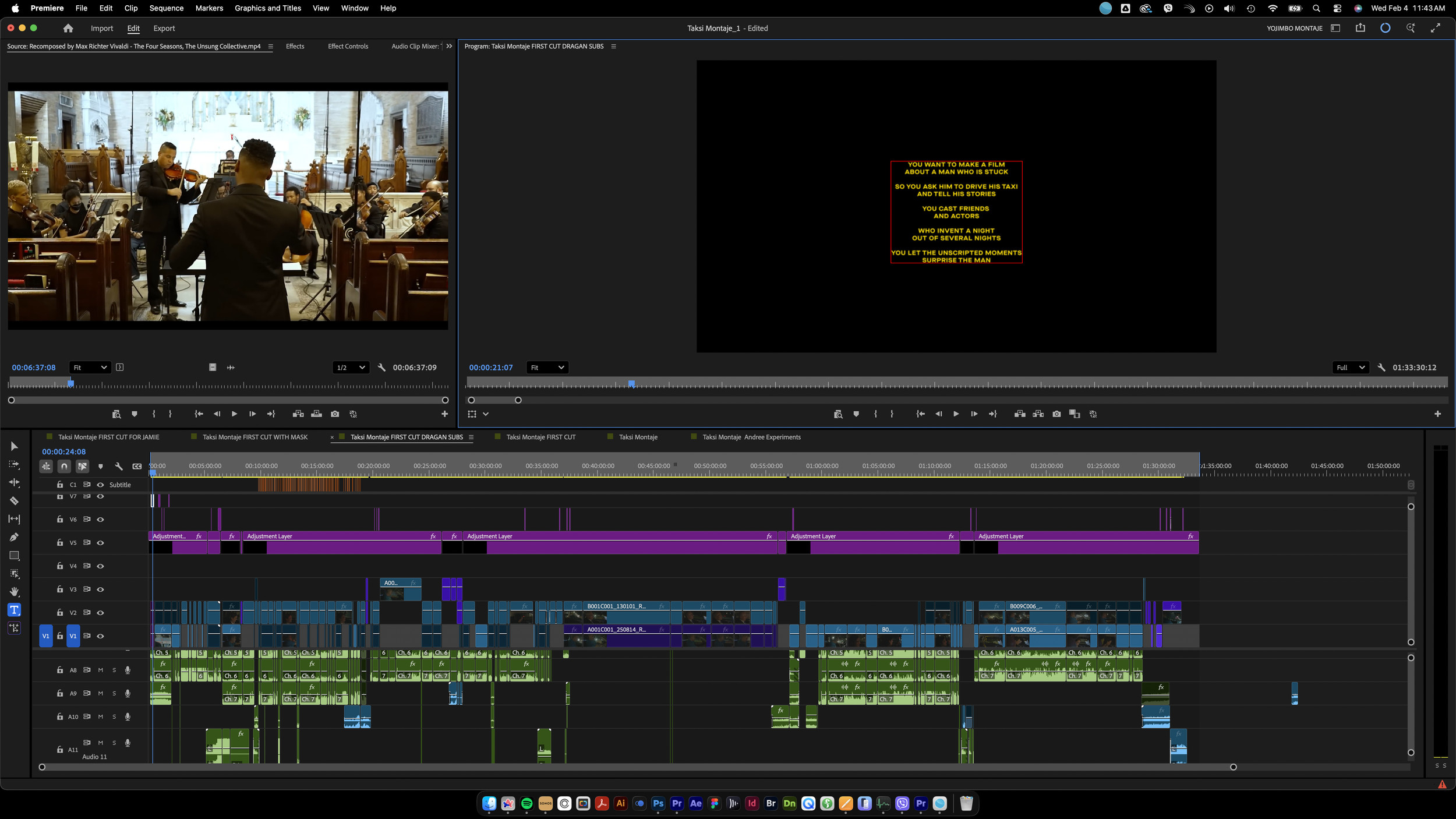

I am finishing an edit of my first feature film, Taksi. It employs a level of visual minimalism that I think is analogous to the above works. It uses repetition and duration to make some kind of statement on the experience of one immigrant right now in 2026, chiefly: entrapment. Because it is film, it is also sociological and about people. Because it is art, I put one camera fixed to the driver of a cab in NYC, and the other, the passengers. I let the changes emerge from the sameness. Like Cartagena's piece, the political implications of my film are implicit; it is about immigration and labor and containment in a place of purported freedom. That the driver in this film is my father is something else entirely.

“Taksi” 2026 Andree Ljutica